Background: There are many colorful stories about Edmonia's life but not much documentation, so it is difficult to get a reliable picture.

Edmonia said her father, Robert Lewis, was a full-blooded negro freeman from the West Indies and a gentleman's servant. There is some evidence to suggest he was born in Newark, New Jersey and that his mother was a freed slave who owned property, even though she was illiterate. Edmonia's biographer thinks Robert went to Haiti looking for conditions more hospitable to his race. While he was there he married and had two children. Then he smuggled his family back into Newark. He may have worked as a servant there.

By 1840, Robert's Haitian wife and daughter had died, leaving only a son aged 8, named Samuel. Robert met Edmonia's mother in the same year.

Edmonia said that her mother, Catherine, was full-blooded a Chippewa, but her biographer thinks Catherine was born in Canada to an African American father, an escaped slave, and a mother who was mixed native and black. In either case, she lived as Chippewa and was skilled in their crafts.

Catherine's family left Canada and went to live near Albany. That's where Catherine and Robert met, and that's where Edmonia was born. It appears that the family lived in town, rather than with Catherine's tribe, but both parents had died by the time Edmonia was 5 and Samuel was 13. They were then adopted by Catherine's 2 sisters and traveled with their nomadic tribe in the area around Niagara Falls selling Native artifacts to tourists. At this time Edmonia was known as Wildfire and Samuel was known as Sunshine. Apparently Edmonia and Samuel lived with the tribe about 7 years.

Edmonia's extraordinary stroke of fortune was that her brother was able to finance her education. At the age of 20, Samuel decided to seek his fortune out west. The mysterious aspect about this is that, before Samuel left, he chose to pull Edmonia out of this tribal life and settle her in a white community, and that he was able to do it. Somehow he had enough means to arrange for Edmonia to board with Captain S. R. Mills, a white man who lived in a white part of town, and to pay for Edmonia's tuition at a private school.

Although the story at the time was that the children lived with the tribe after their parents' death, a Montana newspaper reported much later that Samuel had started working as a barber at age 12, which would imply that he lived in town, probably Albany, as Native American men favored long hair.

Using his barbering skills to make his way, Samuel traveled to San Francisco and the mining camps in Idaho and Montana. In 1868 he settled in Bozeman, Montana, where he set up a barber shop. He prospered, eventually investing in commercial real estate and marrying a respected widow. He apparently contributed to Edmonia's support until she was able to make her own way.

Training: From 1852-1856, Edmonia shed her native ways and attended a private home school with white children.

From 1856 to 1858—age 12 through15—Edmonia attended New York Central College, a Baptist abolitionist school. In this environment, she began to rely on her African-American heritage.

The abolitionists were eager to support a promising young black woman, and when she was 15, they helped her get into Oberlin college in Ohio, the first coeducational and interracial college.

Although Oberlin wished to promote interracial tolerance, black people were a novelty in Ohio in 1859, before the Civil War. Edmonia's presence and her achievements excited animosity in some quarters. In her third year, two white girls became violently ill on a sleigh ride after drinking mulled wine that Edmonia had served them. They accused her of spiking the drink with a so-called aphrodisiac called "Spanish Fly." Since they were on a romantic date, it seems more likely that the men slipped them the aphrodisiac, if that was the cause. The girls recovered so their stomach contents were not examined.

There was insufficient evidence to charge Edmonia, but vigilantes beat her brutally and left her to die in field on a winter night. Edmonia's friends found her and nursed her back to health, but a year later she was accused of stealing art supplies. Rather than continue to deal with incidents of this type, the school barred Edmonia from finishing her course work.

Private life: When she left Oberlin, Edmonia moved to Boston, and, with Samuel's assistance set up an art studio.

By 1865, when she was 21, Edmonia had earned enough money to move to Rome, where she joined the circle of American expatriates and artists, including Charlotte Cushman and sculptor Harriet Hosmer. She adopted an androgynous style of dress, and it is assumed that she had same-sex relationships, but she is never associated with anyone in particular.

After her initial period in Rome, when she hung out with the expat community of artists and established her career, little is known about Edmonia's life.

In the 1870s she made various trips to the U.S. to promote her career, but there is no record of her seeking out her brother, as you might expect.

Apparently Edmonia continued to live in Rome until at least 1887. In that year, Frederick Douglass recorded in his diary that she attended a dinner that he had hosted with his new wife.

After this she disappears from public view. She is thought to have retired to London in 1901; she died there in 1907.

Career: With letters of recommendation from Oberlin addressed to various abolitionists, Edmonia moved to Boston, with the ambition of learning to sculpt. She learned Greco-Roman sculpting from a moderately successful sculptor named Edward A. Brackett, who was well-connected with important abolitionists.

Edmonia's first works were inspired by the lives of abolitionists and Civil War heroes. One of her first works was a portrait medallion of John Brown, a prominent white abolitionist. She sold many copies to his fans.

She then did a bust of Robert Gould Shaw, a white Bostonian who led black troops in the Civil War, that was so popular that she sold over 100 plaster copies. Women writers of the time publicized her work extensively.

|

| Robert Gould Shaw, 1867 |

By 1865, Edmonia had earned enough money to move to Rome, a well-known center for women sculptors. Edmonia told an interviewer that she “was practically driven to Rome" in order to obtain the opportunities for art and culture, and to find a social atmosphere where she was not constantly reminded of her color.

In Rome, Edmonia changed her subject from white abolitionists to figures of African Americans and Native Americans. She celebrated the emancipation of black people with a work called Freedwoman and Her Child (location unknown).

She celebrated her native American heritage with The Wooing of Hiawatha. This was her first life-size group, and it was sponsored by Charlotte Cushman. Tales of Edmonia's nomadic childhood helped raise interest in the piece.

|

| The Wooing of Hiawatha (The Old Arrowmaker), modeled 1866, carved 1872 Smithsonian / Jan's photo, 2010 |

Edmonia became one of the predominant sculptors in Rome. Her work sold for large sums, she won high commissions, and her studio became a fashionable place for tourists to visit.

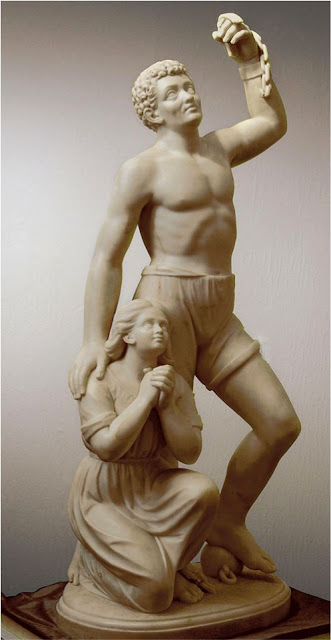

In 1867, Edmonia depicted a powerful image of an African American man and woman emerging from the bonds of slavery. The meaning of the diminutive and submissive female figure is open to interpretation.

|

| Forever Free, 1867 Howard University, Washington, D.C. |

|

| Columbus, c. 1867 High / Jan's photo, 2010 |

|

| Hagar, 1868 Smithsonian / Jan's photo, 2010 |

In the 1870s, Edmonia did some small decorative pieces. The San Jose Public Library has some examples.

|

| Lincoln, Awake, Asleep San Jose Public Library / Internet |

Here's an example of a portrait bust from this period.

|

| Portrait of a Woman, 1873 St. Louis / Jan's photo, 2010 |

In her sculpture of Cleopatra, Edmonia was responding to an earlier depiction by celebrated American sculptor William Wetmore Story. Story's Cleopatra is ideally proportioned, serenely seated, and gracefully garbed; she is merely considering the idea of committing suicide, as symbolized by the innocuous snake decorating her slender wrist.

|

| William Wetmore Story, 1819-1895 Cleopatra, 1869 Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

| The Death of Cleopatra, 1876 Smithsonian / Jan's photo, 2010 |